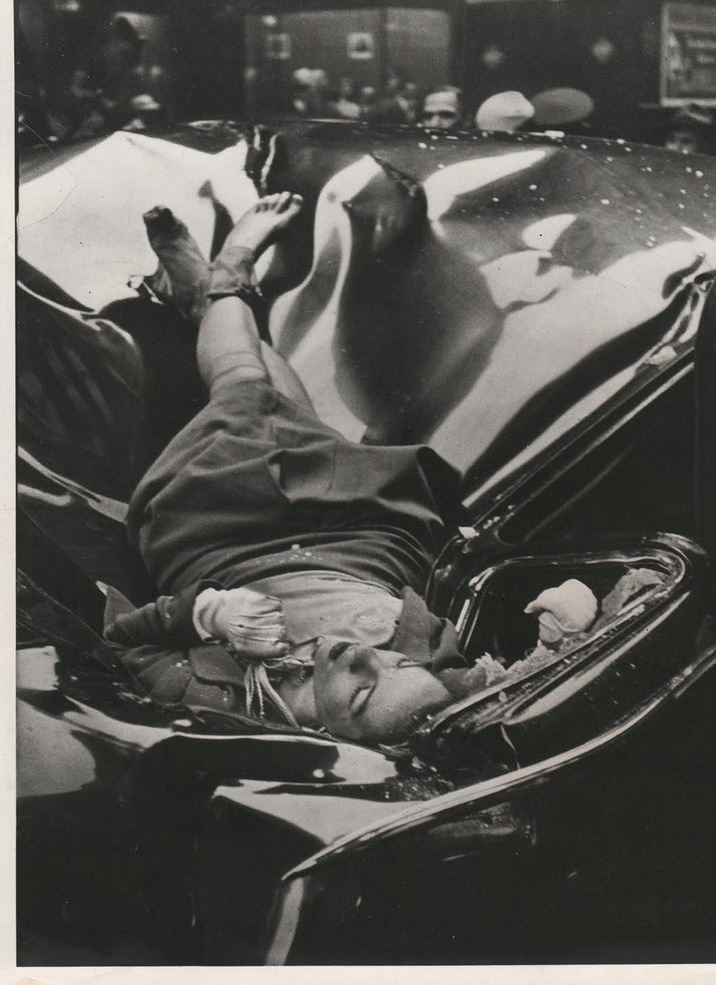

The best known photograph of Evelyn McHale is a portrait of appalling beauty. At first look she appears to be lost in a dream. You might think she has spilled onto a bed with black satin sheets billowing around her. "Maybe she danced her feet sore," you’ll think. Maybe she enjoyed one too many glasses of champagne before succumbing to sleep without even removing her white gloves. In the picture Evelyn lies in elegant requiescence, ankles crossed and head tilted just so. Her fingers reach delicately for the pearls around her neck. And if you didn’t know you might imagine her the envy of her friends, the crush of every boy. If you didn’t know you might think this 23 year old has a life of glamour and good fortune laid out before her.

You might think that. If you didn’t know that minutes before this image was struck Evelyn McHale had been hurtling toward the earth at over 100 miles an hour.

Robert C. Wiles

The black sheets enveloping Evelyn are in fact not satin or soft Egyptian cotton, but the warped steel of a limousine roof come to bear all the violence and the pain of a trouble ridden woman in free fall. More than 1000 feet above on the 86th floor observation deck of the Empire State Building she left behind three personal items before leaping to her death— a coat, a make-up kit holding family photos, and a black leather pocket book. Inside the latter was a note.

It was May 1, 1947 when the train carrying Evelyn home pulled into Penn Station. She had been the night before down in Easton, Pennsylvania where her fiance, Barry Rhodes, was studying at Lafayette College. When she left that Thursday morning there was no sense of despair. Barry would later recall, “When I kissed her goodbye she was happy and as normal as any girl about to be married.” But two hours later upon her arrival in New York she crossed the street to the lobby of the Governor Clinton Hotel (now the Affinia Manhattan) and penned her farewell. Two blocks away stood what was then the tallest building in the world and what had become a magnet for beleaguered souls in search of escape. She made her way toward the skyscraper and took the elevator up. Standing on the observation deck facing north and overlooking Central Park she stepped up onto the parapet. Beyond the city she could see the George Washington Bridge, the Palisades, the Hudson Valley in bloom. She toed the edge and threw herself into the void. A fall from that height would take approximately 10 seconds, a meaningless amount of time to the salesmen and secretaries filing papers behind office windows on the floors below. But to someone falling earthbound at 152 feet per second time is elastic.

One Mississippi. Two Mississippi. Three Mississippi…

The last sound she heard was the rush of wind in her ears screaming a terrible and immutable truth.

Four Mississippi. Five Mississippi. Six Mississippi...

That sometimes the world cannot be made right. Some decisions cannot be called back.

Seven Mississippi. Eight Mississippi. Nine Mississippi...

The crash startled the crowds of shoppers on 5th Avenue. Among them was Robert C. Wiles, a photography student who quickly made his way across the street to shoot what has become known as “The Beautiful Suicide.” LIFE Magazine ran it, full page, with the caption “At the bottom of the Empire State Building the body of Evelyn McHale reposes calmly in grotesque bier, her falling body punched into the top of a car.” Later, Andy Warhol appropriated the image and manipulated it into his famous work, Suicide (Fallen Body).

Hours later Detective Frank Murray discovered the note written by Evelyn shortly after she arrived in Manhattan that morning. It read, “I don’t want anyone in or out of my family to see any part of me. Could you destroy my body by cremation? I beg of you and my family – don’t have any service for me or remembrance for me. My fiance asked me to marry him in June. I don’t think I would make a good wife for anybody. He is much better off without me. Tell my father, I have too many of my mother’s tendencies.” The comment referencing her “mother’s tendencies” is presumed to mean mental illness of which her mother suffered.

Andy Warhol

It is a tragedy that transcends her death, a drama in which none of the actors ultimately got their wish. Her sweetheart would move to Florida and never marry. The boy with the camera would never publish another picture. And the girl who wanted nothing more that morning than to end her life in anonymity became something of a legend in death. Maybe it’s our lurid curiosity, a macabre sort of voyeurism that still draws our eye almost 70 years later. Maybe it’s the perverse balance between composure and ruin. Or maybe, like a mirror, the best known photograph of Evelyn McHale reminds us too much of our own frailty to look away.

Many of the facts contained in this story come from Jim Hughes' well documented piece at Codex99